We are launching a series to address a question many people have about what it means for there to be unequal pay at work, and what laws address the problem. Our focus is on the California Equal Pay Act and the protections that employees in California have. Today we will start with the basics of the California equal pay law, where it was and how it has evolved, and future blogs in this series will cover other pressing aspects of unequal pay in the workplace.

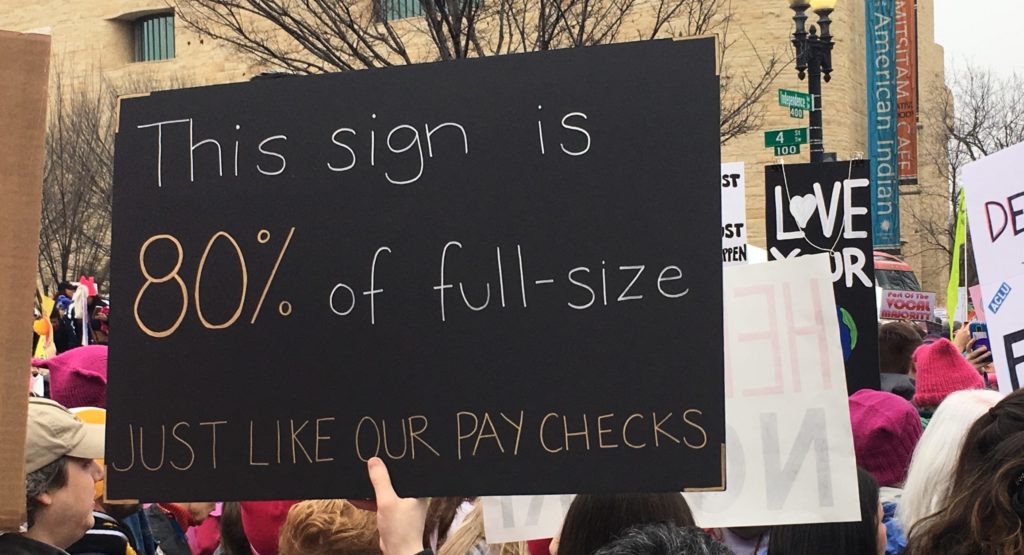

According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, women earned roughly 82 cents for full-time, year-round work compared to every man’s dollar earned at work in 2020[1]. The Institute’s March 2021 report also found even larger gender differences for Hispanic and Black women, at 58.7 and 63.6 cents on the dollar compared to White non-Hispanic men.

For decades, the California Equal Pay Act (EPA) has prohibited employers from paying employees less than workers of the opposite sex for equal work. California’s first Equal Pay Act was enacted back in 1949 as part of Labor code section 1197.5. The original legislation provided:

“No employer shall pay any individual in the employer’s employment at wage rates less than the rates paid to employees of the opposite sex in the same establishment for equal work on jobs, the performance of which requires equal skill, effort, and responsibility, and which are performed under similar working conditions.” [2]

Despite Equal Pay being on the books in California for over 70 years, some employers continue paying women less than male counterparts, all while avoiding accountability.

In recent years, advocates have sought to strengthen the California Equal Pay Act. In 2015, the law was amended by the California Fair Pay Act. The California Fair Pay Act strengthened the Equal Pay Act in several ways. Changes included:

“Requiring equal pay for employees who performed “substantially similar work” when viewed as a composite of skill, effort, and responsibility; making it more difficult for employers to justify inequities in pay through “bona fide factors other than sex;” explicitly stating retaliation against employees who seek to enforce the law is illegal; and criminalizing employers who prohibit employees from discussing or inquiring about their co-workers’ wages.” (California Labor Code Section 1197.5)

Two years later, the California Equal Pay Act was expanded to bar race and ethnic pay discrimination. California enacted Senate Bill 1063 on January 1, 2017, which added race and ethnicity to the existing list of protected categories. These additions forbid employers from paying employees of other races or ethnicities less for substantially similar work. The provisions, protections, procedures, and remedies relating to race or ethnicity-based claims are also identical to the ones relating to sex.

In January 2019, California adopted a law forbidding employers from asking an applicant for salary history information. (California Labor Code Section 432.3.) As a result, today, California employers are banned from using prior salary to justify any sex, race, or ethnicity-based pay differences.

It is important to note that under equal pay law, there are valid reasons an employer might have for paying employees of the opposite sex, or of a different race or ethnicity, differently for substantially similar work. A pay difference can be based on different levels of experience or education, a seniority-based pay system, a merit-based pay system, or a “bona fide factor” other than sex. These reasons can give an employer a valid defense for paying less, regardless of protective status.

While the Equal Pay Act has existed in California for over 70 years, many women and people of color are still disadvantaged in the workplace by poor enforcement of the law. If you suspect your equal pay rights have been violated and are considering your legal options, consult with a seasoned, employment attorney at Valerian Law, P.C.

[1] The Weekly Gender Wage Gap By Race and Ethnicity: 2020 (published March 2021). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2021-Weekly-Wage-Gap-Brief-1.pdf

[2] Stats.1949, c. 804, p. 1541, § 1